Read about it or watch it? An analysis of the BBC News website

March 19, 2011 Leave a comment

With over 14 million unique users a week, the BBC News website is one of the most popular online news sources in the world.

Amongst its many features, the website allows users to see which of its stories are most popular. A box at the bottom of the homepage shows the top 10 most read articles and the top 10 most watched videos (as well as the top five most shared stories).

At a time when there are so many major international stories unfolding (such as the Libyan uprising or the aftermath of the Japanese tsunami), I decided to take a snapshot of the BBC’s most popular stories and compare them.

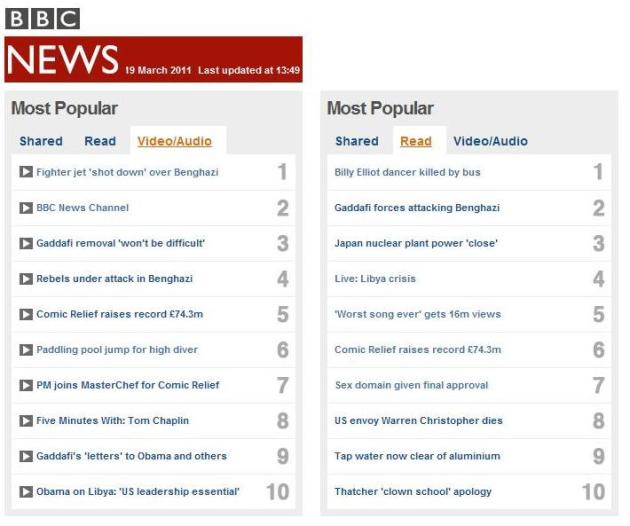

Here are the most watched videos (left) and the most read stories (right) on the BBC News website, on Saturday the 19th of March 2011 at 13:49:

Even at first glance there is a noticeable difference in the make-up of these two lists. The leading story in both is different, with a Libyan story featuring in the number one slot in most viewed and a UK story featuring as number one in the most read.

This is not particularly surprising, considering the dramatic nature of the Libyan jet footage and the fact that the story about the death of the schoolgirl has no accompanying video footage at the time of writing.

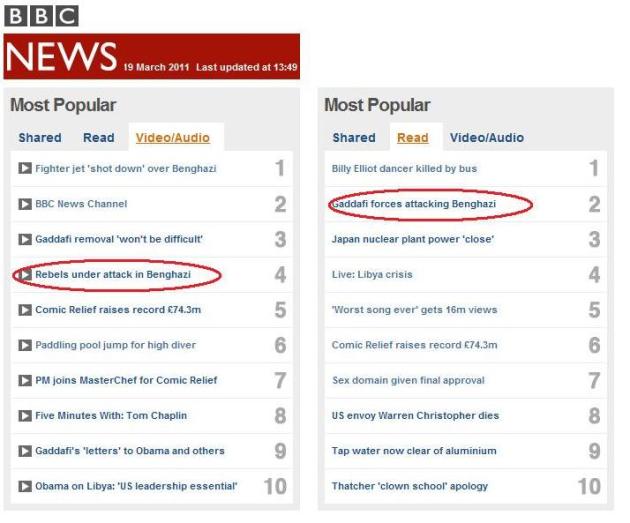

However, when you start to look at the stories that both sections share, some interesting observations can be made. Take a look at this example:

Here, you can see that the story about Gaddafi’s forces attacking Benghazi is the second most read story on the BBC News website, and also appears fourth in most viewed section.

This implies that many users reading the story about Benghazi have then gone on to follow other links with video footage that supplements the Libyan coverage.

In this instance, it seems that online video journalism is supporting the written articles.

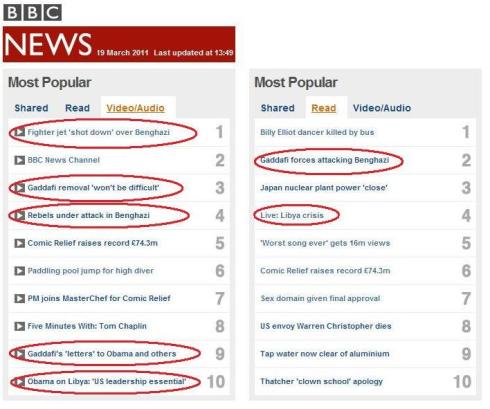

This next image emphasises the popularity of Libya-related stories in both sections:

Again, the fact that more than half of the most viewed stories focus on Libya supports the idea that those reading about Libya are going on to find out more through the medium of video.

But now look at the comic relief story, which also appears in both sections:

This story is almost equally as popular in both formats. Unlike the Libyan coverage, both links are receiving significant traffic, regardless of the medium of the news itself.

Next, have a look at the lack of Japan-related stories on the most viewed section.

Despite the fact that the third most read story on the BBC News website relates to the aftermath of the Japan earthquake, not many people are following the story through video.

This is interesting considering the vast amounts of footage on the BBC News website from Japan in recent days.

What this suggests is that whilst people are interested in reading about what is happening in Japan, they aren’t necessarily willing to pursue the story further through video.

A final observation to be taken from comparing these two lists is where the lighter stories feature. We can see in both the most read and most viewed sections that the celebrity-based or “fluff” stories feature significantly:

Interestingly, whilst the lighter stories make up just under half of the top 10 in both sections, they do all fall in the second half of the list.

What can be gleaned from this is that users will generally gravitate towards the more serious stories, regardless of whether the story is a written article or a video clip.

CONCLUSION

Whilst this is simply a glimpse of the most popular pages on the BBC News website at a single moment, it throws up some interesting ideas:

1) That video journalism can work as an effective supplement to written articles.

2) That what people like to watch doesn’t necessarily reflect what they like to read about (Japan example)

3) That online video journalism is a popular format for a variety of types of news, whether this is hard news or ‘fluff’

In order to get a clearer picture of the relationship between the most watched and most read BBC News stories, the website would have to be monitored over a longer period.

However, what these images do help to illustrate is that the very format of the news (be it video or written word) can determine the actual stories we choose to follow.